By Virginia Garda

At the turn of the twentieth century,

Chicago became the center of a transformation of the urban landscape, most

notably because of the surge of skyscrapers1. The architectural

movement responsible for such innovation was lead by men who were not native to

this city but established their careers in it, and thus they came to be known

as the Chicago School2. The style that they developed was

characterized by an emphasis on both the utilitarian function of buildings and

their aesthetic qualities2, and continued to be influential for

decades throughout the United States1.

The

ingenuity of this group is especially apparent when their architecture is

compared to that of the century preceding it; a series of revivals of older

architectonical styles dominated American architecture throughout the

nineteenth century2, and as a result it was largely derivative and

lacked true originality. Meanwhile, technological developments caused a rapid

development of new forms of civil engineering. Chief among these was the use of

new cast-iron structures to develop arched bridges2. It took a new

generation of bold architects to amend how architectural innovation was

stalling behind engineering and technological inventions.

Chicago

became the ideal gathering place of such a generation because of the

combination several factors. Its population had been growing rapidly since the

1850’s, and the Chicago Fire of 1871 ravaged large portions of the city, which

lead to a high demand for the development of new buildings.2 The

price of land also saw a steep increase2, and thus architects were

obligated to expand vertically instead of horizontally1.

Fortunately, the availability of new technologies such as elevators and the

aforementioned cast-iron structures allowed for the rise of multi-storied buildings1,

and eventually that of the early skyscrapers.

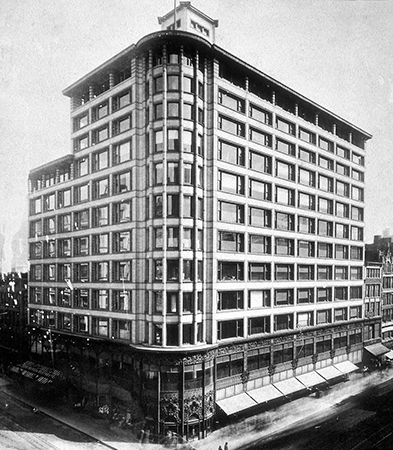

Perhaps

the quintessential architectonical work from this period was the Carson Pirie

Scott Store, which was designed by Louis Sullivan and D.H. Burnham in 18993.

It’s a steel framed building with twelve stories, and features the wide, three

parted windows which came to be known as the Chicago Window3. They

were meant to let in a lot of light into the building, as well as showcase the

merchandise sold by the store. Its exterior was adorned with terra cotta tiles

and bronze decorations, which in addition of being ornamental, were also

practical because of their fire-resistant properties2. This balance between form and function

showcases how Sullivan and his contemporaries were attempting to meet the needs

that modern cities demanded, while continuing to place an importance on the

aesthetic qualities of buildings3.

The

struggle that this generation of architects addressed is not unlike that the

literary modernists faced a couple of decades later. Both movements were caught

in a rapidly-changing world and had to redefine their art forms in order to

address these changes. The modernist authors were writing about urbanization

and urban masses, while the Chicago School had to create a new form of building

in order to solve the problems created by these changes. In addition, while the

literary modernists were attempting to define what the United States

represented through language, the Chicago School managed to create an aesthetic

style that was uniquely American.

It’s

also of interest to talk about the Chicago School in a class about Modernism

because they were responsible for creating the urban landscape that creates the

setting of many of these literary works. Learning about this architectonical style

not only facilitates the visualization of the world these novels were trying to

depict, but also elucidates why the setting of these works was important in the

first place.

Works Cited

[1] "Architecture: The First Chicago

School." Architecture: The First Chicago School. Chicago Historical

Society, 2005. Web. 07 Sept. 2016.

[2] Condit, Carl

W. The Chicago School of Architecture. Chicago: U of Chicago, 1964. Print.

[3] Siry, Joseph. Carson Pirie Scott:

Louis Sullivan and the Chicago Department Store. Chicago: U of Chicago, 1988.

Print.

No comments:

Post a Comment